Despite surviving multiple traumas in their home countries, enduring criminalization in Mexico, and being denied asylum by the United States, these women stuck at the US-Mexico border teach us what it means to joyfully resist.

Violence is a major factor driving women and girls to seek asylum in the US. Many are fleeing toxic environments where gender discrimination is normalized, and where seeking justice can result in retaliation or even death. They are driven by the desire to no longer live in a state of constant fear and to be recognized for their worth as human beings.

“A lot of people still have the idea that migration is mostly men, but what we are seeing is that it’s mostly families and a lot of women—like single moms with children, a lot of teenagers [and] unaccompanied minors—who are migrating,” says Paulina Olvera Cáñez, director of Tijuana-based Espacio Migrante, an organization that provides services for and advocates for the rights of migrants, refugees, and asylum seekers.

Their journeys are long and treacherous, and many of these women face more discrimination, violence, and criminalization along the way. Two such women, Katerine and Joy*, agreed to share their migration stories with Oxfam. They were driven from their home countries by sexual assault and violence, and their journeys have brought them to the border city of Tijuana, Mexico, where they work as community organizers for Espacio Migrante.

Katerine's story

Katerine started her journey in August 2018. In her home country of El Salvador, she and her sister experienced incidents of gender-based violence and violence that caused them to rethink living there.

“Unfortunately, this is a common problem in El Salvador,” says Katerine. “The violence is just too great right now. Gangs control the country, and the government can’t really control the situation.”

Reporting these incidents only makes matters worse. “[Reporting] is twice as bad because the government isn't advocating for the people or looking out for the well-being of the community,” she explains. “If people report, it's going to be looked at as if they're telling on the gangs.”

Katerine’s entire family decided to flee. “We didn't really have a destination in mind,” she says. “We were just trying to save our lives.”

They initially headed to Guatemala, and while they were there, they experienced more violence. The owner of their hotel had refused to pay gang members the extortion payment they demanded; Katerine’s family was awakened in the middle of the night by men with guns. Her family decided they would be safer in Mexico.

Once there, the Mexican Commission for Refugee Assistance directed them to Mexico City to receive psychological and medical attention. According to Mexico’s National Human Rights Commission, migrants in the country are constantly subjected to crime, xenophobia, and extortion by local police and other authorities. Unfortunately, Katerine and her sister experienced this firsthand. One day, they witnessed a robbery at the store where they worked. They filed a complaint and the police responded with retaliation, harassing them to make them retract their report. They had been putting up with mistreatment from locals who viewed migrants as criminals, and once they started receiving threats from the police, they’d had enough.

The family determined they would be safest in the United States, where Katerine’s older sister lived , so they made their way to Tijuana to cross the border. Under President Trump’s “Remain in Mexico” program, they were forced to return to Mexico while pursuing their asylum claim in the US. Although the Biden administration formally ended this program, the process of unwinding it has been incredibly slow, and thousands of asylum seekers remain stuck in dangerous conditions in Mexico.

“For six months, we had to go to court, and it was a strenuous process,” she says. “The experience was one of suffering, bad treatment, and humiliation.” They had filed for asylum as a family, but their cases were separated since Katerine and her sister are adults. Eventually, the family decided it was more important to stay together than come to the US, so they abandoned the process.

Katerine and her family were served five-year deportation orders barring them from entering the US, which means they are unable to visit her sister and her two young nieces. “If I could change one thing, it would be the deportation order,” she says. “It’s completely unfair. I never lived inside the US, yet I have a five-year deportation order. I’m not a criminal.”

With no hope of reuniting with her sister in the US, she turned her attention to the migrant community. During their legal battle, the family had been living in Espacio Migrante’s shelter, and after a short time, Katerine became a leader among her peers.

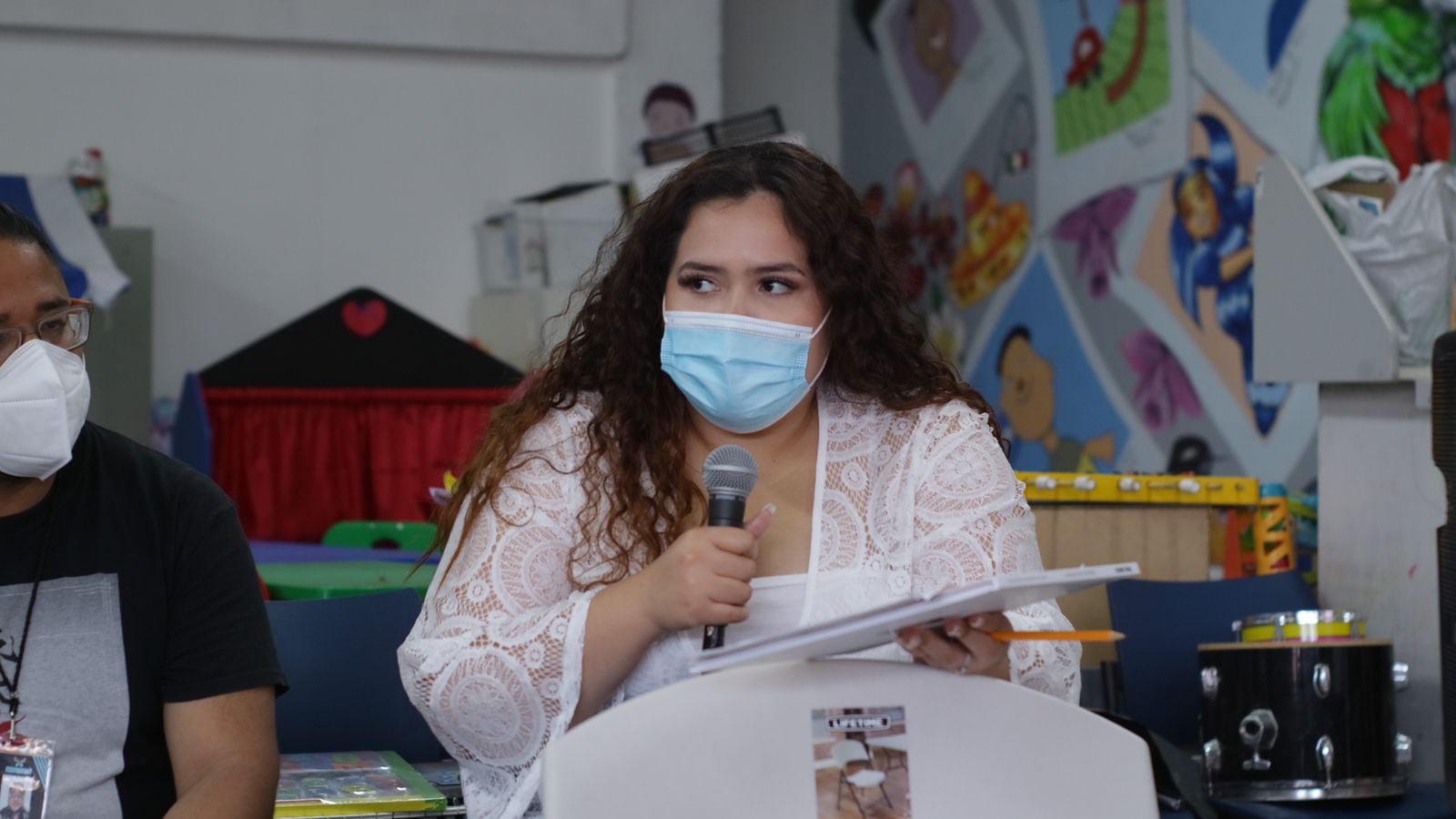

Now a lead community organizer at the nonprofit, Katerine has been involved with their pandemic response. She connects participants with resources and educational programming and organizes forums. At one such forum, a team from Universidad Iberoamericana heard her story and offered her a scholarship. She begins her studies in August and plans to become an immigration attorney in Mexico, using her experience to fight the injustices in the asylum system.

“The migrant community is a strong and resilient community,” she says. “I’m happy to contribute to it.”

JOY*'s story

Joy’s journey began in Cameroon in October 2018. When conflict broke out between the military and rebels, she lost her home and all of her possessions in a fire, and her family—including her uncle, brother, and children—fled to her grandmother’s house. The chief of her village advised her to leave the country on her own—assuring her that her children would be safer with other family members.

The chief gave her $50,000 Central African Francs (around $91) to cross to Nigeria. What she found in Nigeria was darkness, she says. She was blackmailed into sex work. After a month of forced prostitution, she found someone who was willing to help her, and she able to get a plane ticket to Ecuador, where Cameroonians could visit without a visa due to a diplomatic agreement.

In early 2019, she arrived in the capital city of Quito with no money and no support system. There, she faced discrimination as a Black woman and a migrant: she was denied jobs and exploited by employers who refused to pay her. Unable to make money, she slept in a park with others who had fled Nigeria.

After a few months, she’d had enough. “In Ecuador, I was not accepted,” she says. “But I am smart. I speak Spanish, French, and English. I decided I would have a better life in America.”

She set off on foot to Tijuana. The journey took about three months. By the time she reached Tijuana, it was early 2020 and COVID-19 was starting to spread. She was directed to Espacio Migrante, which provided her with shelter, psychological services, a community of fellow migrants, and most importantly, a sense of security.

Now she works as an organizer for Espacio Migrante. “I'm so proud to be an organizer because I know the reality for the people,” she says. “I had to abandon my babies. I was traumatized. I was suffering. Now it’s important for me to give respect and love.”

From the shelter, Joy has been able to reconnect with her children. She hopes to bring them to Tijuana; once they are reunited, she will decide her next steps.

“I know many people do not want migrants in their country,” she says. “Migrants are not the problem. We are not coming to make trouble in your country. We come because we need someplace secure.”

How can you support women like Katerine and Joy?

“Joy and Kathy are literally fleeing for their lives and not necessarily even looking for the American dream, but just trying to find a safe space. As much as we want it, Tijuana can’t be that safe space,” says Espacio Migrante Director Olvera Cáñez

Every day, countless people like Katerine and Joy face gender-based violence and persecution that forces them to leave their homes in search of safety and security. They have little hope of protection from their own governments, who are frequently complicit in or indifferent to the violence. Many are subjected to further violence in Mexico and other countries of transit as they make their way to the US.

It’s time for President Biden to fix the US asylum process to provide lifesaving refuge to people fleeing persecution because of their gender.

*Name changed